Utopia

Politics

It is no coincidence that the first great modern history book on the USSR, published in 1982, was entitled “Utopia in Power” by its authors, Heller and Nekrich. Ever since the foundation of the Soviet regime in 1917, the Revolution it had sprung from had carried both hope and political and economical upheaval, born in the 19th century, that was meant to create a “new man” and lead to the ultimate goal of a stateless, egalitarian society. Yet after Stalin’s death, in 1953, the “triumphant” march of the Socialist economy was thrown into question. Because of Stalin’s emphasis on investment in heavy industry rather than consumer goods, housing and whole sectors of agriculture, the daily lives of citizens of the Soviet Union and of its “brother countries,” became ever more difficult. The system clearly needed reform. Khrushchev attempted to put it into place with his plan of “developed Socialism,” all the while maintaining the masses’ support for the project of a new civilization born in 1917. This is why official discourse about the creation of a new man, raised with the sole purpose of taking part in a society of production, educated to conquer space before the great American rival, loyal to the Communist Party and ready and able to build modern new cities did not fade away until the 1980s. However, as the regime weakened, the population of the Eastern bloc adhered to this utopian project less and less. Instead they dreamed increasingly of a society inspired by the Western model.

Archive

East German postcard illustrating a matchbox inspired by the Cosmos Soviet Utopia

In the midst of the Cold War, the Space Race was one of the major stakes in the rivalry opposing the USSR and the United States, both from a military and spatial-technology point of view and for its ideological propaganda value.

country: German Democratic Republic / year:

In the midst of the Cold War, the Space Race was one of the major stakes in the rivalry opposing the USSR and the United States, both from a military and spatial-technology point of view and for its ideological propaganda value. Soviet achievements from 1953 to the mid 1960s are recalled on this matchbox: Sputnik, the first satellite to orbit the Earth, in 1953, followed a month later by the first living creature in space, the dog Leika, and finally, the successful launch of a manned space flight, which put Yuri Gagarin in space on April 12, 1961. Soviet space conquests would go on, but the United States would eventually catch up, then in 1969, pass them in the race to the moon. After that, the Soviets began specializing in building Mir and Saliout space stations

Subbotnik, the Saturday volontary work

Subbotnik – from the Russian subbota, or “Saturday,” meant "voluntary" unpaid work on Saturdays. The concept got started in 1920 in the USSR.

country: Soviet Union / year:

Subbotnik – from the Russian subbota, or “Saturday,” meant "voluntary" unpaid work on Saturdays. The concept got started in 1920 in the USSR. According to Communist theory, since the working class had come to power, and exploitation and private property had been abolished, this work was performed for the collective good. It helped unify the masses, abolished weekday hierarchies and advanced Socialist ideals "concretely," so it did not need to be paid. In the 1950s, subbotniks developed particularly in East Germany, the “showcase” of Socialism for the West. In practice, the masses’ enthusiasm for clearing forests and building collective buildings was limited, insofar as it was essentially forced unpaid labor. By the late 1980s, this "voluntary slavery" was generally limited to having to devote a day or two a year to clearing snow or participating in a spring-cleaning campaign.

Official report on the new town of Volgodonsk

The construction of the Atommash factory of Volgodonsk on the Volga

country: Soviet Union / year:

The construction of the Atommash factory of Volgodonsk on the Volga in 1980 responded to the necessity of lowering energy costs in the production of a nuclear economy. This factory for nuclear-reactor parts was intended to attract thousands of young people and their families ready to start a career in the nuclear industry. To this purpose, official propaganda praised the merits of a “perfect city,” sprung from the Earth at the same time as the factory, providing entertainment for children as well as ideological mentoring for youth thanks to the komsomol. Wide avenues and vast blocks of low-rise buildings corresponded to the esthetics of the new Eastern city.

Anti-capitalist propaganda: A Romanian family tells the story of its life in the United States

For many years, Romania had been seen by the West as a regime slightly apart from the other Communist-bloc countries

country: People’s Republic of Romania / year:

For many years, Romania had been seen by the West as a regime slightly apart from the other Communist-bloc countries, thanks to its capacity to distance itself from the USSR. However, in the early 1980s, the country was weighed down by considerable debt. The state lost the support of the population and only remained in power through vicious repression of its opponents orchestrated by the Securitate, the political police. It soon became necessary to convince Romanians of the merits of the Romanian Socialist economy. Hence this propaganda document in which the “American experience” is perceived as a dangerous illusion in which debt and market laws destroy all hope of a better life.

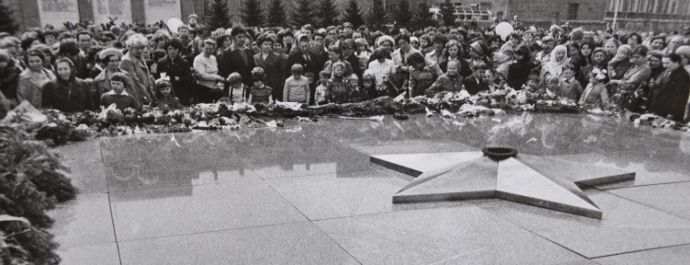

The demolition of the statue of Lenin, Bucharest, March 5, 1990

Communism has a very classical vision of art and of its role in public spaces

country: People’s Republic of Romania / year:

Communism has a very classical vision of art and of its role in public spaces – consequently, it is perfectly natural that popular anger in 1989-1990 played itself out against the political iconography that was such an integral part of the landscape. The style was Socialist Realism, as opposed to abstraction. It had imposed itself as early as the 1930s in the USSR, and after 1945 in the satellite states. These more or less massive statues were three dimensional declinations of the ideological litany, with its patron saints (Lenin, Marx, Engels), its national leaders (Gomulka in Poland, Thälmann in Eastern Germany, Gottwalt in Czechoslovakia), its monuments to the dead, its empowered workers and happy families populating Socialist cities. National celebrations were held at their base, and newlyweds would come to have their wedding pictures taken there. After 1989, some countries would protect them as vestiges of a lost era (Germany) or transform them into historical parks (Hungary, Russia). In others, the statues would be destroyed in haste or sold to collectors around the globe.

Socialist education in East Germany: the creation of a “new man”

Since the 1950s the basis of education in East Germany had rested on the emergence of a new “Socialist citizen”

country: German Democratic Republic / year:

Since the 1950s the basis of education in East Germany had rested on the emergence of a new “Socialist citizen,” fit to become a “producer,” blindly loyal to the regime he was responsible for perpetuating. Thus the State’s goal was not bettering students’ lot, but rather political control over them. Indeed, every class had a small group of students (usually selected from among the best) elected to form a “group council,” a sort of political model for the other children. In addition to school activities, youth mentoring was also carried out through political, athletic, cultural and scientific “work communities.” Once again, the goal was to orient children towards a Socialist work community. Despite this, historians have shown that this “educator state” did not always succeed in shaping youth, which began rejecting the politicization and militarization of their education in the late 70s and early 80s.