Minorities

Society

Communism was meant to be not only egalitarian, but internationalist, too: the idea being to create a class-less, nation-less society. In reality, established in December 1922 and revised more than once, the Soviet Union’s federal and institutional framework recognized the existence of both federated republics (15 by 1956) and autonomous ones. Although they had no political sovereignty, they did have cultural rights… as well as their own autonomous regions – small ethnicity-based administrative units. In actual fact, from the very beginning, the violence of the centrifugal movements agitating the former Tsarist empire worried the Bolshevik leaders, who did not want to see the new Russia reduced to its heartland. Thus the armed invasion of the territories that reconstitute the Tsarist empire – this being one of the key goals of Stalin, “the little father of the peoples”. Furthermore, behind the superficially federal system, actual power remained very centralized, and the Republics’ and regional administrations’ responsibilities relatively limited. Moreover , the vast majority of the Republics, theoretically organized on national bases, had minorities whose territorial assignments were the direct result of a desire to limit or even prevent nationalist expression within the Federated Republics. This, for instance, was the case of the Armenian enclave of Nagarno-Karabakh, which was deliberately incorporated into the Republic of Azerbaijan. The different Soviet regimes’ attitudes towards minorities betrayed a certain ambivalence. On the one hand, official discourse extolling friendship between peoples should have encouraged respect for ethnic groups from the Baltic States to Central Asia, from Siberia to the intertwined populations of the Balkans. On the other, the strong nationalist tendencies amongst these far-flung regimes led the Soviet Union to centralize power and assimilate minorities, or even “Russianize” them, in the case of the USSR. These practices, far from abolishing nationalist sentiment, reinforced and fed ethnic and cultural protests that would later contributed to the implosion of the Communist states.

Archive

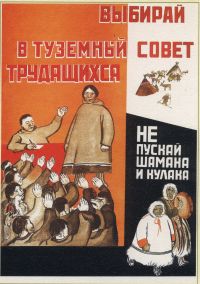

Poster about collectivization for reindeer herders in Siberia

“Vote for the proletarians, keep the shaman and the Kulak from entering the local consul!"

country: Soviet Union / year:

“Vote for the proletarians, keep the shaman and the Kulak from entering the local consul!" From its inception, the Communist project aimed to go global. Limited to the USSR by the 1920s, it nevertheless spread to the very edges of the “Soviet empire,” – even reaching Siberian reindeer herders. A central element of Communist propaganda, collectivization was also a powerful tool for Sovietization, i.e. both for political subjugation (as in Ukraine during the 1920s and the Baltic countries after World War II) and cultural assimilation.

Estonia, 1987. The Hirvepark

While the Baltic states’ incorporation into the USSR started out cautiously in the years just after World War II, the beginning of the Cold War marked the start of brutal Sovietization.

country: Soviet Union / year:

While the Baltic states’ incorporation into the USSR started out cautiously in the years just after World War II, the beginning of the Cold War marked the start of brutal Sovietization: along with the purges, forced collectivization and mass repression came measures isolating the local elites, destruction of monuments to their war dead and restriction of the use of native tongues as a demonstration of the will to disintegrate national cultures. Far from succeeding, this policy reinforced the populations’ hostility towards “the Soviet occupant”. By the late 80s, Baltic society had begun its struggle against centralized Soviet power. In 1987, for the first time, the three countries became the stage for popular strikes. The Communist authorities were at a loss, because on the one hand, the strikes did not address political matters directly (the banners here simply declared the names of the Baltic countries in their native tongues), and on the other, brutal repression was no longer an option in the context of Gorbachev’s glasnost.

Friendship between peoples

“The Great Stalin is the standard bearer for friendship between peoples in the Soviet Union.”

country: Soviet Union / year:

“The Great Stalin is the standard bearer for friendship between peoples in the Soviet Union.” On November 15, 1917, the Bolshevik revolution proclaimed “the declaration of rights of the Russian Peoples.” From its very inception, the regime thus announced its intention to put an end to the “people’s prison” of the Tsarist empire and to set up a society devoid of classes and nations. As it proclaimed its rejection of imperial practices, the idea was for Soviet regime to establish its authority by seeking to obtain voluntary adhesion of the different peoples of the new Russia. Throughout its existence, the USSR, from its European boundaries to Siberia, from the Far North to Central Asia, would include friendship and recognition between populations as a theme in its propaganda.

Disorders in Alma-Ata, the capital of Kazakhstan

De-Stalinasation brought changes to the unified, centralized schema which had been largely imposed by force

country: Soviet Union / year:

De-Stalinasation brought changes to the unified, centralized schema which had been largely imposed by force: greater liberty regarding culture and language was granted; after a period of Russianization, local leadership was encouraged once again. But during the 60s and 70s, nations and nationalities remained subjected to a severely unifying mold. Like during the Tsarist period, recognition of rights and national identities varied depending on the will of the central government. The Gorbachev years represented a real turning point: the end of censorship and re-found freedoms incited “centrifugal” nationalist protests as early as 1985-1986. Some of them were violent, like here in Alma-Ata, the capital of Kazakhstan. In 1990, one after another, the Parliaments of the 15 Republics seceded and, in December 1991, the USSR could no longer avoid implosion.

The Hungarian minority crisis in Rumania

In south-east Europe, the state borders inherited from two world wars no longer coincided with the mosaic of populations

country: People's Republic of Hungary / year:

In south-east Europe, the state borders inherited from two world wars no longer coincided with the mosaic of populations. In many Eastern-Bloc countries, despite official speeches about friendly relations between nations, the issue of minorities remained open to debate. In Hungary, for instance, the problem of Magyar minorities living in neighboring states resurfaced during the last twenty years of the Communist period. Initially cultural, the definition of Hungarian identity eventually took a political turn. Following the Helsinki Accords (1975) , the discourse about cultural nationhood became entangled with the idea of supporting human rights, as, for example, when the issue was defending Magyar dissidents in Czechoslovakia or denouncing crimes perpetrated against the Hungarians (notably the destruction of villages) by Ceaucescu’s Communist and nationalist dictatorship in Rumania. Mobilization redoubled in 1988-1989, when Hungary was confronted with a massive influx of refugees (some 25,000), for the most part people of Hungarian origins fleeing Ceaucescu’s regime.

Ida Nudel, a dissident jew imprisoned in Siberia

From Tsarist times all the way to the implosion of the Soviet Union, anti-Semitism was always very strong in Russia

country: / year:

From Tsarist times all the way to the implosion of the Soviet Union, anti-Semitism was always very strong in Russia: the Bolshevik Revolution and World War II represented brief interludes in the persecution. While Russian Jews enjoyed a small “thaw” immediately after Stalin’s death, anti-Semitism – disguised as anti-Zionism – resurfaced during the last years of Khrushchev’s rule, and under Brezhnev as well. The same themes reemerged: Israel, part and parcel of “world imperialism”, was trying to organize a “fifth column” in the Soviet Union, while international Jewish organizations represented “the reactionary Jewish bourgeoisie” and were agents of the “worldwide Jewish conspiracy.” Despite the repression, a specifically Jewish dissidence arose, which demanded the right to leave the country. Ida Nudel’s story illustrates the “Refusenik” movement, which was only partially successful. Born in 1931, Ida Nudel first asked to emigrate to Israel in 1970. When confronted with the Soviet authorities’ refusal, she engaged a struggle that led to for four years of exile in Siberia – where she continued her struggle. It was not until 1987 that she finally obtained an exit visa.