Arts

Culture

While the Russian Revolution originally supported the artistic avant-garde, which was seen as revolutionary, art was gradually made to toe the ideological line, and came to be considered as a tool of the proletariat to serve the revolution (in the struggle against bourgeois art) and socialism (to glorify the Soviet regime’s achievements). Socialist realism, through which the Party aimed to control culture and thought, reached its apogee after 1945, during the Cold War, when it was adopted by the people’s republics. All of the arts were under the control of official state structures, and artists who rebelled were censured and oppressed. De-Stalinization, in 1956, and Khrushchev’s “thaw” opened a period of greater artistic freedom, which lasted until 1962 in the Soviet Union and the late 1960s in most of the other Eastern-bloc countries. Non-official art that was open to outside influences flourished during this time. When the government took back the reins during Brezhnev’s “ice age,” accusing non-official art of serving the bourgeoisie and the West, independent art was forced back into private spaces. Among official artists, some gave their unconditional or barely critical support to the powers that be, while others tried to maintain a certain artistic freedom from politics. A few chose freedom of expression in exile in the West, while others who were censored, jailed or forced into exile, chose internal dissidence, with the support of the West.

Archive

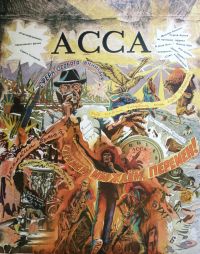

Poster for the film ASSA, by Sergei Soloviev (1988)

Shot in Yalta in 1986 by Sergei Soloviev, Assa is a cult film from the Perestroika period

country: Soviet Union / year:

Shot in Yalta in 1986 by Sergei Soloviev, Assa is a cult film from the Perestroika period, as the USSR’s cultural policies began easing up in the late 80s. While purportedly portraying a detective story involving a mafia man representing the old oligarchy, his mistress and the young rocker she falls in love with, Soloviev was actually shooting a documentary about the underground rock scene in Leningrad. The plot was just a pretext for the concert scenes that brought groups like Kino, whose song “I Want Change!” – as sung by their lead singer Victor Tsoi – became the unofficial anthem of Perestroika.

Socialist sculpture in city centers

In the heart of Dresden, Lenin marches towards a radiant future, followed on either side by two worker-fighters and a red flag.

country: German Democratic Republic / year:

In the heart of Dresden, Lenin marches towards a radiant future, followed on either side by two worker-fighters and a red flag. This huge monument was slightly raised, in order to be visible from afar, provide a welcoming place for mass rallies, and imprint its ideological strength on individuals’ minds. The rest of the square was laid out in relationship to the statue (note the mural in the background). One sign of the monument’s importance is that it was commissioned from a Soviet artist, while East German artists had to settle for smaller, less-ideologically important subjects (happy families, workers, union members etc.). These statues were located in city centers, along major arteries where official parades and high-ranking leaders’ cars would pass by, but also in the newly built residential neighborhoods. After the fall of the Communist regimes, Moscow, Budapest and Estonia created memorial parks with their toppled Socialist statues.

Art education for children

The Eastern-bloc countries always invested a lot in art education.

country: Soviet Union / year:

The Eastern-bloc countries always invested a lot in art education. Schools, conservatoires and academies depended on the State, which served a dual purpose: making sure that teachers toed the ideological line (teaching only Socialist realism and arts from earlier times) and proving Socialism’s superiority by making culture accessible to the masses and developing a home-grown artistic elite that could triumphinternationally. There were counter-performances, like the celebrated violoncellist Mstislav. Rostropovich, who became a symbol of the struggle for freedom and was forced into exile in 1974.

The Russian intelligentsia in exile

In the 1970s, international pressure led to certain Soviet dissidents

country: Soviet Union / year:

In the 1970s, international pressure led to certain Soviet dissidents including Alexander Solzhenitsyn (1974), Leonid Plyushch and Vladimir Bukovski (1976) – being freed and allowed to leave. Until then, they had been interned, but some of their clandestine writing had been smuggled to the West (e.g. The Gulag Archipelago,1973). Once in the West, they wrote, founded journals and did public speaking(conferences, television). They informed the West about the reality of Soviet totalitarianism, inspiring some French anti-totalitarian “nouveaux philosophes,” like Bernard-Henri Levy and A. Glucksmann).

An art opening at a private home in Moscow

With de-Stalinization (1956), an independent artistic milieu

country: Soviet Union / year:

With de-Stalinization (1956), an independent artistic milieu, open to international art and scornful of the ideology of Socialist Realism came into being, first in the USSR and then in the people’s republics. This liberalization ended abruptly in the 1960s, condemning the artists concerned to censorship (Milan Kundera), dissidence and prison (Vaclav Havel), or clandestine expression and shows in private homes (like the Polish conceptual artists). Whether by choice (Roman Polanski) or by force (P. Kohut), many went into exile in the West, where they could create and express themselves freely.

Political theatre: Vaclav Havel’s Audience

The play Audience (1975), distributed by samizdat

country: Czechoslovakia / year:

The play Audience (1975), distributed by samizdat, was a conversation between a dissident writer sentenced to manual labor in a brewery (as Havel had been), and an alcoholic brewer, whom life under Communist had reduced to despair. Dissident artists and intellectuals, portrayed by propaganda campaigns as bourgeois parasites, were cut off from the masses for many years. Censorship and repressionenlarged that gap greatly, forcing artists to withdraw into discreet, private places or to go into exile. Very few artists were in fact dissidents or openly dared to use art as a means of expressing their politicalactivism.

Nationalist artist Bohumil Riha’s speech against Charter 77

In the people’s republics, art was by definition state-sanctioned, an ideological weapon to defend Socialism

country: Soviet Union / year:

In the people’s republics, art was by definition state-sanctioned, an ideological weapon to defend Socialism within the framework of the Cold War. Art teachers were kept under strict control, as weremuseums and exhibits. Western avant-garde currents in art were rejected in favor of Socialist realism. Artists were enrolled in official organizations, without which it was impossible to display, perform or publish one’s work in public or, therefore, to earn a living from one’s art. In exchange for state support, artists like Bohumir Riha were obliged to defend their nation and its regime against dissident artists.

Vladimir Vyssotsky sings “Save Our Souls”

Vladimir Vyssotsky (1938-1980) was a famous Russian actor of both stage and screen

country: Soviet Union / year:

Vladimir Vyssotsky (1938-1980) was a famous Russian actor of both stage and screen. Despite the huge popular success of his songs, he was never officially recognized as a singer by the Soviet authorities. Vyssotski’s somewhat politicized songs, which described daily life, circulated under the table. His marriage to the French actress Marina Vlady allowed him to travel to the West, where he recorded. Refusing to move to the West, he defined himself as being in disagreement but not a dissident. He can be compared to the East German singer Wolf Biermann, who was deprived of his nationality and was forced into exile in 1976.